History of Iran’s textile industry and ancient textiles in Iran Our knowledge of clothing in ancient Iran mainly comes from drawing images on stone reliefs, metalwork (including coinage), seal motifs, and from around the 2nd century AD and wall paintings. The information is scattered and episodic and related to the ruling families, army, gods and sometimes priests; Depictions of women (even female goddesses) are rare.

History of Iran’s textile industry and ancient textiles in Iran Our knowledge of clothing in ancient Iran mainly comes from drawing images on stone reliefs, metalwork (including coinage), seal motifs, and from around the 2nd century AD and wall paintings. The information is scattered and episodic and related to the ruling families, army, gods and sometimes priests; Depictions of women (even female goddesses) are rare.

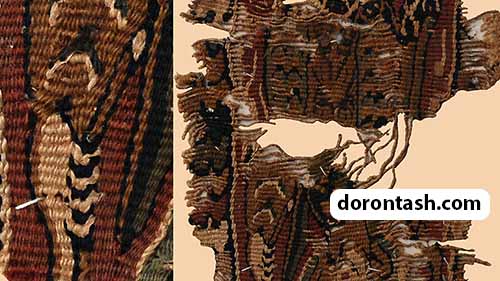

Elamite Textiles and Clothing (2750-653 BCE) At its height, the Elamite Empire controlled the region east of Mesopotamia to Central Asia and Pakistan, but after 1100 BCE, the empire’s political influence declined. Early Elamite cylinder seals show bearded men (probably princes or priests) with layered skirts, leather bands, or hides similar to those depicted on certain statues from Mari (the ancient city of Syria). ) can be seen and clay tablets show that wool and linen were exported to neighboring lands. A few seals (ca. 1600-2200 BC) include female figures with similar skirts but fuller and more fluted.

But a bronze statue (now in the Louvre) of Queen Napirasu (1333 BC) in Susa, wearing a long-sleeve diagonal shirt, a long bell-shaped skirt with wide bands around the waist and bottom left side, and has a deep fringe (probably wool) around the edge, found.

Post-Elamite rock reliefs (e.g. Mount Farah, c. 800 BC), although seriously eroded, indicate long-sleeved, ankle-length dresses with dropped collars. which covered the shoulders. Achaemenian textiles and clothing The Achaemenid family of Iran conquered the Medes in the northwest of Iran and occupied the lands that stretched from the Balkans to the Tianshan Mountains in Central Asia and China until the destruction of Alexander the Great. Persepolis, the ceremonial capital, provides the most pictorial evidence of clothing; Scholarly opinion exists as to whether details from the Oxus hoard (British Museum) and clothing remains from other Central Asian sites such as Pazyryk should be considered Persian-Achaemenid or Central Asian clothing.

The relief motifs of Persepolis and the Susa (Louvre) tiles do not show anything of women’s and children’s clothes, but two distinct men’s clothes: the “Madin” dress of long pants, which is in ankle boots, a A tunic below the knee, and a long-sleeved coat (candis) over the shoulders, and a tall, furrowed hat, enclosed by a band of metal. And the “Persian” dress, a skirt up to the ankles, a collar with four large folds at the elbow, and a tall and flaky hat (probably made of feathers or mat-like layers). This dress has recently sparked controversy.

By rejecting a theory from the 1930s that this garment is not made of a rectangle of fabric and is designed on the shoulders and belts are used to form the edges of the fabric; Anna Russ argued for the intricate construction of two separate pieces: a back-swept cape with a triangular insert at the elbow creates pleats in the sleeves, and a sari-like skirt is shaped with strips of fabric hanging down the front, back, and sides. . Two decades later, P. Beck (1972) proposed another construction based on two lengths attached to the shoulder, both cut differently, to produce distinct sleeve curves and edges. Neither theory is entirely satisfactory regarding the skirt, as described for the detailed figures.

Fabrics and clothes of Parthians or Parthians

The various silk roads that passed through Asia flourished during the Parthian period, bringing Chinese silk to the West to be exchanged for horses, wool, and linen. Cotton, in a short time, may have been grown in the east of Iran, but it was made available from East Africa and the Persian Gulf regions.

Most of the detailed information about clothing from this period is gleaned from pictorial art from the ancient cities of Palmyra, Dura, Hatra, and Nimrud Dag, as well as from central Central Asia such as ancient Syria, ancient Iraq, and ancient Anatolia—but modern specialists in these areas Often such clothes are evaluated as “national” clothes instead of “imperial” clothes.

High-ranking men wore waist- or mid-thigh blouses with long, tight sleeves, yet Palmyran sculptures show a draped, looped, and knotted cloth. There were different ways of fastening the tunic, possibly indicating differences in rank, status, or perhaps office: There was a wide diagonal opening on the left side, a wide round collar, a square collar and an open collar from the neck to the bottom of the left shoulder. The shirt sometimes had heavy curtain-like pleats that formed a U-shaped apron, and a long, slim-sleeved jacket was worn over this shirt. Baggy trousers, often designed to be gathered at the mid-calf, were gathered either at the ankle or into tall boots that reached the calf.

A long silk band on the left shoulder, which was shown on the face in some images, may indicate the priest’s dress. Regarding headgear, gods, kings and generals (such as those at Hatra and Nimrud Dag) are depicted with tall hats with a narrow front, decorated with pearls. has it.

There is little information about women’s clothing. The Greek kiton is said to be the inspiration for Palmyran dress, but the women’s shirt in the Achaemenid period wall decoration shows a tight dress with an open or semi-closed collar, decorated with a series of additional materials on the band around the chest. Underneath this was worn a long pleated skirt, and a long, wide white shamil or cloak covered the shoulders or fell over the arms.

Fabrics and clothes of the Sasanian period

Since the fifth century, Iranian cotton was exported to China along with linen and wool. In the history of the Chinese empire, silkworms were smuggled to Central Asia in 419 BC, but Arab history and Persian poetry show that the agricultural industry was established in Sasanian lands around 300 BC. Drawing weaving technology was known from the eastern Mediterranean lands, but most linen fabrics were still made on the short loom. The texture of the carpet (slit) and the texture of the mixed twill are related to Sasanian woolen fabrics and silk fabrics, respectively.

Stone carvings near Shiraz show the king in a close-fitting torso, perhaps of molded leather, with full-length trousers or long wavy haired pieces of sheepskin or very fine cloth. By the middle of the 4th century, a long tunic-like apron was worn, reaching the lower part of the thigh, and some later silver vessels depict another type of shirt with pointed corners. In the late 5th or early 7th century—depending on the date of the carvings in Taq Bostan—the royal dress was a long-sleeved shirt worn with a long silk blouse, or decorated with figures or thin layers of patchwork. A double row decorated the center front of the dress, the neck, buttons and smooth edges. Underneath, loose pants were worn and soft boots were tied with a long ribbon. Each king had a distinctive crown, often consisting of a large “balloon” (probably of hair), while princes and generals had tall hats with a small Phrygian curve leading to a bird or animal head, or with A prominent icon was decorated in a special style.

Zoroastrian goddesses, Anahita, and court entertainers provide the most information about women’s clothing. In the late 3rd century AD, as Rostam, Anahita wears an ankle-length robe with distinct pleats and a fur ribbon belt. However, in Taq Bostan, which was carved at least 150 years later, he wears a long sleeved robe and a long sleeved coat (probably in a slumped position) over his shoulders. Her long, hanging hairdo is more than what female musicians used to do when hunting.

On Sasanian period metals, the female dancers attract attention for their long robes that reach to their thighs. In a rare depiction of royal ladies, the dress is similar to those worn by Anahita, while the children wore miniature versions of the royal piece.

During the Sasanian era, Zoroastrian religion was officially promoted and Zoroastrian priestly dress was probably formalized during this period. The religious regulations regarding the lamb’s wool kousti (belt) and cotton sandra (shirt), which were worn by all adult believers, were probably formulated during this period. In a rare depiction of royal ladies, the dress is similar to those worn by Anahita, while the children wore miniature versions of the royal piece. During the Sasanian era, Zoroastrian religion was officially promoted and Zoroastrian priestly dress was probably formalized during this period.

The religious regulations regarding the lamb’s wool kousti (belt) and cotton sandra (shirt), which were worn by all adult believers, were probably formulated during this period. In a rare depiction of royal ladies, the dress is similar to those worn by Anahita, while the children wore miniature versions of the royal piece. During the Sasanian era, Zoroastrian religion was officially promoted and Zoroastrian priestly dress was probably formalized during this period. The religious regulations regarding the lamb’s wool kousti (belt) and cotton sandra (shirt), which were worn by all adult believers, were probably formulated during this period.

Sassanid Empire

The Sasanians created an empire roughly on the borders established by the Achaemenids, with the capital at Tisophon. The Sasanians made a conscious effort to revive Iranian traditions and eliminate Greek cultural influence.

Their rule was characterized by considerable centralization, ambitious urban planning, agricultural development, and technological advances. The Sassanid rulers adopted the title Shahnashah (King of Kings) as a rule over many petty rulers, known as Shahrahs. Historians believe that society was divided into four categories: priests, warriors, scribes, and commoners. Family princes, petty lords, grand lords, and priests together formed a privileged class, and the social order seemed rather rigid.

Sasanian rule and social classification system were strengthened by Zoroaster, which became the state ritual. Zoroastrian religion was very powerful. The head of the priestly class, Mobed, along with the military commander, Oran Sepahbod, and the head of administrative formalities, were among the great men of the government. Rome, with its capital at Constantinople, had replaced Greece as the main enemy of western Persia, and hostilities between the two empires were frequent.

Shapur I (240-272 BC), the son and successor of Ardeshir, launched successful battles against the Romans and in 260 AD he even captured the Valerian Empire. Between 260 and 263 AD, he had lost his victory to Ornatus, an ally of Rome.

Shapur II (who ruled between 309-379 AD) regained the lost lands in three successive wars with the Romans. A stone relief in Rostam Naqsh depicts Shapur’s victory over the Roman emperor Valerian and also shows the image of Philip Khosrow I of Arabia (531 AD), also known as Anushirvan Adel, one of the famous Sassanid rulers. He reformed the tax system and revamped the army and bureaucracy, bringing the army closer to the central government than to local rulers. His reign saw the rise of digans (literally meaning village rulers), small landowning nobles who later became the backbone of the Sasanian state administration and tax collection system. Khosrow was a great builder who upgraded his capital, established new cities and built new buildings.

He rebuilt the canals and rebuilt the farms that had been destroyed in the wars. He built strong fortifications at the border crossings and carefully settled the tribes in selected cities on the border so that they could act as guardians of the state against invaders. Justinian paid him 440,000 gold pieces as a bribe to keep the peace, but he seems to have been a man who enjoyed the fruits of peace and saw no reason to continue the pointless war.

He was loyal to all religions, although he ordered Zoroastrianism to be the official state religion, but he was not unduly disturbed when one of his sons became a Christian. Under his supervision, many books were brought from India and translated into Pahlavi. Some of them later entered the literature of the Islamic world.

The reign of Khosrow II (1380-628) was characterized by the splendor and extravagance of the court. Towards the end of his reign, his power waned. In a renewed battle with the Byzantines, he enjoyed early victories, captured Damascus, and captured the Holy Cross in Jerusalem.

But the attacks of Heraclius, the emperor of Byzantium, brought the enemy forces to Sassanid territory. In the spring of 633 AD, Khosrow’s grandson named Yazdgerd sat on the throne, and in the same year, the first Arab squadrons began their first invasion of Iran.

The years of war tired both the Byzantines and the Iranians. The Sassanids were weakened by declining economic power, heavy taxes, religious unrest, rigid social stratification, the growing power of malkan rule, and the rapid turnover of rulers. These factors facilitated the Arab invasion in the 7th century.

This was the beginning of an end. Yazdgerd was a person who was at the disposal of his advisers and was unable to unite a large country that had become several small feudal kingdoms and was collapsing. Rome was a threat. This threat was caused by the regular armies of Khalid bin Walid, who was once one of Muhammad’s chosen companions and now after the death of Prophet Muhammad, he was appointed to lead the Arab army.

The beauty hidden in the history of Iran’s textile industry

The textile history of Iran, the recorded history of civilization in the modern era of Iran goes back to the third millennium BC and their textile production is even older. This area, which is located between the Caspian Sea in the north and the Persian Gulf in the south, has now been formed as a commercial area and a thousand-year-old cultural center. This country has witnessed the rise and fall of many weak dynasties, powers, and their various influences, all of which have left distinct cultural signs in the art of this region, which gives a unique look and history to Iranian textiles. It is impossible to forgive and repeat it. In this article, we will take a look at some examples of Iranian textiles in the Nazmiyal collection and examine their cultural context and significance.

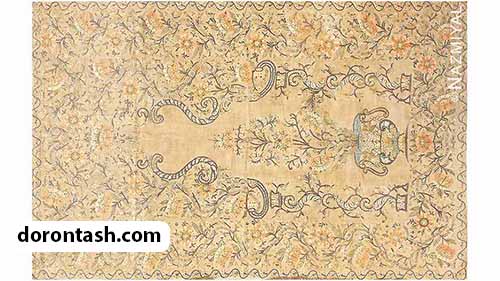

Iranian antique fabric (17th century AD)

This embroidered fabric was woven in the 17th century, at the height of the Safavid Empire in Iran. The Safavid period is considered by historians as a glorious time for the creation of works of art in the region, because the rulers of this dynasty allocated huge sums of money for cultural enrichment and industrial works supported by the government. The Safavid era began in Iran at the beginning of the 16th century. The Safavid rulers were able to unite the different lands of Iran and strengthen their power by creating new military and political structures in the region. As a result, a unified culture was created with a specific style of architecture, artwork and handicrafts. The surviving textiles and fabrics from this period are considered as part of the most brilliant embroideries and carpets in the history of this region. Many of them are floral with symbolic cypress trees and shrubbery, while others feature human imagery, giving viewers a glimpse into the clothing and lifestyle of 16th and 17th century Iranians. Textiles created during this time period were used as decorative fabrics as well as clothing. It is recorded that wealthy members of the Safavid court were proud of the silk and embroidered clothes they owned, and Shah Tahmasab I (1514-76) is said to have changed his clothes up to fifty times a day.

Antique Iranian silk textiles (mid-19th century AD)

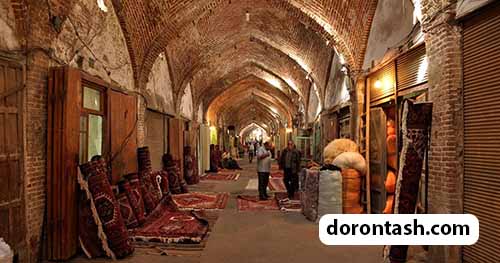

Although the Safavid dynasty is considered as one of the greatest dynasties in the history of Iran, but in the middle of the 18th century, more than one period of seven major conflicts and five decades of war, which had brought the life of the people of the region to chaos, the fall did Because of this, the creation of works of art declined in the 18th century, although textiles still existed on a smaller scale. At the beginning of the 19th century, a new ruling family, the Qajars, came to power. This family had the task of rebuilding an empire that had been destroyed by civil war and unrest, and at that time a member of the French embassy had nicknamed Iran “a vast cemetery”. In order to establish themselves as the Muslim rulers of the turbulent region, the Qajar family carefully considered their image to be similar to the high-ranking leaders of the past, from the decorations of luxurious palaces to the luxurious and bejeweled clothes. The dynasty, which lasted until 1925, excelled in using art as propaganda to consolidate their power. The Qajar high court employed many skilled tailors to show off their wealth, and the production of the Iranian textile industry once again reached a peak of prosperity and exquisite detail. Although tailors were employed by the courts, weaving and embroidery was still a rural industry in the region, and contracts were assigned to various skilled weavers in cities such as Kerman, Isfahan, Tabriz, and Kashan.

During the 19th century, most textiles in Iran were sold locally. While Western Europe was increasingly interested in acquiring territory in the Middle East, this interest in purchasing finished products from the region did not last until the end of the 20th century. The important issue of this trend was Russia, which has been the main importer of Iranian goods and textiles since the beginning of the 19th century. The Russian market for Persian ikat and cashmere continued to increase in demand from the early 1800s. The influx of fabrics made by European factories in Iran caused a lot of damage to the Iranian textile industry from the 1840s, because they were much cheaper than the fabrics made in Iran, but they could be printed with the same patterns that matched the taste of Iranians. become The kings imposed heavy import taxes on European goods to help Iran’s textile industry, but for a while it seemed that Iran’s textile industry in the region would never recover from imports of cheap European goods. The situation worsened when a severe famine at the end of the 19th century killed a third of the population of South Pars and 284 textile workshops in Isfahan were closed. The region seemed to rely on European imports for survival.

Iranian Qashqai coat (20th century)

Although the textile industry in Iran was hit hard at the end of the 19th century, weaving and embroidery were still popular handicrafts, and luxury Iranian fabrics and clothing were still in high demand from Iranians who could afford to buy them. This coat is an example of such a luxurious garment. Archalaqs were worn only by the wealthiest members of society and were embroidered with intricate details such as metallic thread. The long sleeves of this coat were worn to the wrist with straps, buttons or open and hanging on both sides. The sleeves were braided for a short time to allow the wearer to hide his hands between them, a sign of respect in the presence of a high-ranking official. Ironically, although the Iranian textile industry was declining, European taste for Persian rugs and carpets increased in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and exports to Europe and America steadily increased. Despite Iran’s troubled past, it cannot be denied that the region’s textiles are some of the most beautiful and delicate in the world.

The state of the textile industry in Iran

Textile production in Iran dates back to the 10th millennium BC, and most of Iran’s weavers have been rightly praised as masterpieces. The first European-style factory in Iran was established in the 1850s, and they were among the first institutions in this country that used new technologies. In the 19th century, most of Iran’s demand for textiles came from imports, mainly from India, which produced a wide variety of cotton fabrics. There was also some broadcloth for the high end market. Due to the wide availability of raw materials (silk, cotton, wool, linen) in Iran, spinning, weaving, and weaving formed almost universal employment. However, during the 19th century most of Iran’s domestic textile industry first slowly and then rapidly disappeared because it could not compete with cheaper imports from India and Europe (especially Britain and Russia). To prevent this onslaught, efforts were made to introduce modern textile mills that promoted imports. In 1850, spinning and weaving factories were built in Kashan and Tehran, respectively; And in 1859, a spinning factory was built in Tehran. With a shortage of technicians and a technical infrastructure, Iran was dependent on importing these resources, which added to investment costs. This first attempt created a model for the manufacturing sector of the economy that would be characterized over the next 150 years by import substitution, imports of technology and technicians, and government subsidies. Early textile factories could not benefit from government support due to the Treaty of Turkmenchai (1828). The agreement imposed a flat import tariff of 5%, effectively preventing Iran from supporting its nascent industries through high import tariff barriers. Finally, in the 1920s, Iran negotiated new economic agreements with its trading partners, and textile mills and other state-owned enterprises immediately received government support through tariffs and non-tariff barriers. While these early efforts were costly failures, the silk oil factory established by Amin Ali Zarbin in 1884 was successful.

Textile production continued to play an important role in Iran’s economy, but despite the rapid growth of new factories in the 1930s, it remained a rural industry. In 1923, the Amin Ali Zarbin silk factory was reopened, and in 1925, Watan textile factory started production in Isfahan. Between 1931 and 1938, at least 29 large-scale textile factories were funded by the government and private investors. The center of Iran’s textile industry was established in Isfahan with eight workshops (5,372 workers), followed by Yazd with two workshops (1,074 workers), Kerman (696 workers) and Sari (3,396 workers) with one workshop.

Stretch and hosiery industries, wool cleaning, cotton cleaning, and other textile-related industries have also increased their capacity and workforce. In the 1930s, 32 hosiery factories (1,584 workers) and 12 small wool cleaning factories (225 workers) were established. Most of the cotton ginning industry that developed at the beginning of the 20th century was located in Khorasan, the main cotton producing area.

Until 1931, Iran had 26 textile factories with an average workforce of 25 workers per factory. By 1940, the number of spinning factories increased to 76 factories (1500 workers). Private capital was focused on the development of the textile industry. Before launching the first development program, government textile factories, Behshahr textile factories in Qaimshahr, Chalus silk factory and jute processing factory were also in Qaimshahr. In 1940, modern textile mills employed 24,500 workers, compared to only 1,000 workers twenty years earlier. In 1948, these factories were still working. 26 weaving and spinning factories with 188,000 spindles had a production of 10,800 tons per year. The equipment of all the textile factories needed repairs and replacements, and thus productivity was low. Weaving elastic and cotton thread were imported, and cotton and wool fibers were used to create warp and weft by the carpet industry.

In 1949, the domestic production of the textile industry, more than 55% of which was produced by hand, met only 40% of the national demand. At the same time, 30,000 handloom weavers could not compete with imports and became unemployed, which negatively affected the employment of about 120,000 workers. After World War II, the government realized that it needed to repair and modernize old factories and develop new textile factories. Therefore, he promoted private and public investment. Factory production costs were high due to high overhead, lack of maintenance, broken equipment, and poor management, leading to low productivity. Textile sales peaked after 1950 due to renewed economic activity. Domestic demand for cheap fabrics was high, but not at the top end of the market.

Between 1945 and 1958, consumption doubled while capacity increased by only a third. This industry, which was under the pressure of high costs and inefficient production methods, could neither compete with cheap imports nor meet the increasing demand; And the supply of cotton was not always enough. The profitability of textile production increased with high prices due to import restrictions. In addition, the availability of foreign currency enabled the purchase of modern technology, which contributed to greater profitability by increasing labor productivity and reducing capital requirements and

The attraction of huge profits stimulated the building of new textile factories. The government led the construction effort, increasing the number of factories from 13 to 52 between 1956–57 and 1957–60, more than doubling the workforce. However, few efficient factories co-existed with old factories with worn-out machinery under poor management. Private factories had problems competing with newer, state-owned enterprises.

The first ones did not upgrade their technology and some of them were forced to close down. In addition, the new factories were allowed to lay off additional workers, while the old ones were not. As a result, the new wage bill was 35-50% less than the old bill. However, in 1957, 40% of the total output was produced by handloom weavers, who employed about 70% of the industry’s workforce.

Smaller companies and artists who could not afford modern technology suffered from the pressure of profits. Lower prices led to increased demand, which in turn led to industrial development.

In 1955, there were 51 textile manufacturing companies, 41 of which were based on cotton products. The total number of spindles was 370,000 (90% cotton) and there were 5,000 looms and looms (85% cotton). In 1959, the output of this sector was about 200 million meters, of which more than 60% was produced by 26 modern factories. Wool spinning and weaving were concentrated in Isfahan and Tabriz, and the workshops continued to produce cheap materials for clothes, blankets, and army uniforms. There was also some production of cheap synthetic materials for women’s clothing and veils, which negatively affected the sales of woven silk products.

This industry continued to grow until 1961. Between 1950 and 1962, the number of spindles almost doubled and the number of textile machines almost tripled. In 1961, the recession caused demand to fall short of supply; Many factories were closed and the industry asked the government to ban textile imports. Between 1962 and 1966, the government banned foreign investment. Due to excess capacity, this industry sought to export and in 1972, it was able to export 6% of the total production of cotton textiles. The import ban was lifted in 1969, when rising incomes led to increased demand.

By 1972, the number of spindles had increased to 900,000 and looms to 17,000, resulting in the employment of 145,000 workers, doubling the workforce employed in 1962. The garment industry employed 70,000 workers in 1975. In the 1970s, excessive inflation of the economy had a negative impact on the competitiveness of this industry. As wages soared, this labor-intensive industry suffered from high production costs.

Rising domestic demand reduced competition, which was only partially revived by the reduction of import tariffs to sharply lower prices, and by the temporary lifting of import restrictions to address shortages of raw materials and finished products. However, the industry continued to grow due to high domestic demand and strong government support. In 1979, the textile industry faced less competition than in 1969.

In 1980, the number of spindles was 1.4 million and the number of looms was 35,000. This growth was considered a great achievement, as the industry suffered from poor management and limited technical expertise—in short, limited resources—though often private. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, national factories became bigger and between 1980 and 1988, the government imposed a price control system on the industry. Since all inputs were supplied at subsidized prices, the industry was able to maintain its previous production level.

During this period, the domestic textile industries faced many problems such as old equipment, lack of spare parts, inability to import needed parts and raw materials, as well as labor problems.

There were no new investments and no development plans were implemented. After 1988, price controls and input subsidies were reduced, causing price reductions and output declines. This situation was exacerbated by cheap Asian textiles imported through the Kish Free Trade Zone, which remained competitive despite high import tariffs. After the Islamic revolution and further nationalization of the industrial sector, due to the unwillingness of private investors, insufficient investment was made. Also, the government believed that the existing capacity is sufficient to meet the domestic demand.

Between 1980 and 1993, production capacity grew. This industry was completely dependent on the import of machinery and technology, whose development was limited by foreign exchange restrictions. Then the government invested to establish two companies to assemble spinning machines; But this decision only changed the shape of the problem, because these assembly companies also needed foreign currency exchange. After more than a century, Iran’s industrial textile production was still not competitive, although it benefited from domestic production, wool, and cheap, albeit poorly trained, labor.

In the 1990s, yields increased due to rising incomes and tighter protection measures. In 1993, the number of spindles was 1.5 million and the number of looms and looms was 40,000. It is estimated that about 420 workers, which is 30% of the total industrial workforce, work in the textile industry. Most of the workers worked in cottage workshops, which included unlicensed workshops for handwoven carpets and small sewing shops. Fabric and industrial clothing production was the largest employer among other industries with a workforce of about 150,000 people.

Iran’s textile industry consists of companies that are active in spinning, weaving, stretch weaving, dyeing, and printing and use natural and synthetic fibers to produce all kinds of woven and stretch woven fabrics. The main textile items are blankets, hand-woven carpets, machine-made carpets, different textures of wool, as well as cloth and clothing. In 1998 and 1999, 30 factories were producing blankets, but their production capacity reached 15.5 million blankets, which indicated the export potential.

Between 1984 and 1993, the average annual yield of machine-made carpets was 7.7 million square meters, and the amount of serge and felt was 22.5 million square meters, much less than the demand of 122.5 million square meters. It was estimated for the year 2000. Iran has a strong fabric production industry, 21 factories in this field produce 43 million square meters per year.

Between 1984 and 1993, annual production declined significantly, but efforts were made to reverse this trend and even become a silk exporting country. It was estimated that between 1996 and 1997, about 55 million pieces of cloth were produced in Iran. Many workshops have official licenses from the Ministry of Industry and Mines, but there are many unlicensed workshops that produce a large amount of clothing. In 1996 and 1997, Iran exported 19,312 tons of clothing worth 210 million dollars. Low labor costs have provided a competitive advantage for this sector.

Among other textile items produced in Iran, hand-knitted clothing is the most important and prominent product for export in the future. Many workshops have official licenses from the Ministry of Industry and Mines, but there are many unlicensed workshops that produce a large amount of clothing. In 1996 and 1997, Iran exported 19,312 tons of clothing worth 210 million dollars. Low labor costs have provided a competitive advantage for this sector. Among other textile items produced in Iran, hand-knitted clothing is the most important and prominent product for export in the future. Many workshops have official licenses from the Ministry of Industry and Mines, but there are many unlicensed workshops that produce a large amount of clothing.

In 1996 and 1997, Iran exported 19,312 tons of clothing worth 210 million dollars. Low labor costs have provided a competitive advantage for this sector. Among other textile items produced in Iran, hand-knitted clothing is the most important and prominent product for export in the future. The textile industry often produces fabric wholly or partly from cotton, which is sourced from domestically produced cotton. Cotton production increased until the end of 1975, when production reached 716,000 tons of unnecessary cotton. Since then, production has declined due to government intervention and low prices for cotton.

This process was accelerated by the collapse of large and mechanized cotton estates after 1979. Cotton production plummeted to 204,000 tons in 1981, forcing the government to ban cotton exports. Nevertheless, cotton production continued to decline, and Iran even had to import cotton, while the price of cotton yarn increased. However, due to government reform measures, production has been growing ever since.

In 1993, the price of cotton increased worldwide and became an incentive for more production in Iran. In 1995, ginned cotton production increased to 15,000 tons per year, and in 1997 production reached 598,000 tons, of which 35,000 tons were exported. Recently, cotton exports decreased and in 2002, only 3,200 tons were exported. Iran also imports cellulosic fibers (eg, viscose), although there is capacity to produce synthetic fibers as well.

However, the petrochemical industry is not yet developed enough to sustain the synthetic fiber industry. Therefore, the fiber industry is dependent on imports and the availability of foreign exchange restricts its development. Investment in the petrochemical industry has changed this situation by reducing dependence on synthetic fiber imports. This allows both industries to now operate at higher capacities than in the past.

Although Iran’s wool production is very high, most of its products are used by the hand-woven carpet industry, and Iran uses low-quality imported wool to produce woolen fabric. Iran has 102 cotton factories that produce 24,000 tons of wool yarn every year; Home industry produces an equal amount. After pistachios, hand-woven carpets are the most important non-oil export items of Iran. In 1998 and 1999, Iran exported its handwoven carpets worth 570 million dollars. However, in recent years, Iran’s handwoven carpet exports have decreased due to fierce competition from other countries.

Iran has a large antelope population, which has made it one of the largest producers of cashmere: about 1,500 tons out of a total world production of about 8,000 tons. However, until recently, Iran did not have the proper facilities to process cashmere and therefore exported all the soft wool in raw form. This represents a significant loss of revenue, as Iran could earn ten times more than it currently does by exporting Kashmiri wool (99% pure wool). If it was able to produce silk thread, its income would increase by 10%. This amount can be doubled through the production of Turkish clothes.

Over the past few years, investment has increased to capture this added value. Iranian Kashmir Company is the largest wool cleaning and wool washing center in Iran.

Jute is produced domestically. In 1947, the annual requirement was 10 million square meters, of which 75% of jute was needed for the production of rice bags, sugar, flour and cement, while the rest was used for cotton twine and packaging of other products. Double-layer bags, single-layer bags for domestic trade, and second-hand bags for thick materials, especially coal, were used to carry export cargo.

Most jute was woven with a width of 140 cm and cut into pieces with a length of 100 cm and then sewn into bags 70 cm wide and 100 cm long. The bag in Rasht weighed about 750 grams and those woven in sari weighed about 800 grams. Most jute was grown around Rasht, although attempts were made to grow it around Dezful. Some jute and woven georgette fabrics were also imported from India.

Two jute mills were producing. It was the first private factory in Rasht that had modern Scottish machines with 2100 spindles and 80 looms. The factory works in two 8-hour shifts and can produce 4.5 million meters of fabric per year and use 3,000 tons of fiber. The Surrey State Factory, equipped with modern Scottish machinery, had 1,280 spindles and 60 looms and produced 3 million meters of cloth. Both of them produced 4000 kg of yarn and rope. Both workshops were in good condition, but needed repairs. It was planned to establish a small and privately owned factory with 30 weaving machines in Dezful. By 1973, jute production reached an average of 4,000 tons per year, enough to ensure production self-sufficiency. Since 1973, production has decreased to an average of 1,000 tons per year, while demand has been increasing.

There are four spinning and weaving units that produce jute and are more than 40 years old. They do not have a favorable economic and industrial situation. Their nominal capacity is 28,500 tons. Among their other products are jute thread and bags, but the raw materials are imported from abroad. Domestic consumption of jute products, most of which are imported, reaches 85,000 tons per year. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, during 1996 and 1998, Iran’s average annual import reached 53,800 tons, which represented 5.3% of the total world trade in jute. As recently as 2002, Iran protected its jute industry against imports by restricting import laws. Iran also produces a significant amount of silk, all of which is located in its carpet weaving workshops around Qom, Isfahan, Kashan and Nayin

. Chalus factory was closed in 1958. In the 1960s, it was restarted and equipped with 7,344 spindles and 220 looms. The company produced more than 500,000 meters of cloth in 1970, which was more than double the domestic demand. In 2000, production reached 800 tons. In November 2003, the only silk thread factory in Iran, in Soemasera near Rasht, was closed due to the illegal export of cheap silk thread. However, the plant has already been in the red for three years. According to the statistics of the Ministry of Industries and Mines, the overall output of Iran’s textile industry (7000 textile units) constitutes 6.5% of added value, 7.8% of national industrial production, 19.3% of employment and 10% of industrial exports. . In 1995 and 2000, synthetic fibers and recycled cellulose fibers were 1.2 and 1.5% of imports, respectively; All other textile products for which statistics are available constitute less than 1% of total imports. In 1999, some clothing (0.2 percent) was exported.

In 2001, the former state of Iran’s textile industry was blamed for the poor results of cotton production. That same year, the government responded by helping textile exporters, which received $200 billion in annual subsidies. In 2001, textile production increased by 30 percent, but exports increased by 15 percent to $220 million, and in 2002, it even increased by 45 percent. To compensate for this situation, the government hopes to modernize Iran’s textile industry through joint ventures with foreign companies in Japan, Germany, China, and South Korea, mostly through extending low-interest loans to private Iranian textile companies for purchase.

The required equipment is raw materials and technical expertise. The government provided $500 million in preferential loans to modernize its textile industry in Iran. In July 2002, it was announced that 31 textile factories would be transferred to the private sector; An action that was taken with the official policy of privatizing the entire textile industry in order to become more competitive in the world market.

The pressure of the world market was already felt, because in 2000, about two million meters of fabric were illegally imported into Iran. At the same time, the government continued to invest in new government capacity. In August 2003, the largest textile factory in Iran was opened in the city of Fermahin, near Arak, with a production capacity of 8,000 tons per year. Currently, Iran’s textile industries are facing many problems such as lack of liquidity and lack of foreign currency for importing raw materials and spare parts; old and worn out machines due to the impossibility of modernizing production lines, increasing wages; And finally, industry inefficiency.

Not only the domestic threads, but also the goods that are imported to meet the domestic demand for clothing at a low price due to low purchasing power are of low quality; So that the final product is also of low quality. Large exporters are facing macroeconomic problems, especially in relation to foreign exchange problems and lack of active and adequate government regulations.